Longwood Reimagined: A New Garden Experience

/Interior View, West Conservatory. Image by Ngoc Minh Ngo. Courtesy of Reed Hilderbrand.

By Jourdan Cole, Longwood Gardens

Longwood Gardens, America’s greatest center for horticultural display, will unveil Longwood Reimagined: A New Garden Experience to the public on November 22, 2024, celebrating the final stage of the most ambitious revitalization in the Garden’s 100-year history. Led by the acclaimed architecture practice WEISS/MANFREDI in collaboration with eminent landscape architecture firm Reed Hilderbrand, Longwood Reimagined expands the public spaces of the renowned central grounds adding new buildings and new landscapes across 17 acres.

The grand opening will be celebrated with two weeks of festivities, including member-only preview days and special events. Longwood Reimagined debuts in conjunction with the Gardens’ renowned holiday spectacular, A Longwood Christmas, featuring more than half a million twinkling lights across hundreds of acres and festive fountain shows, which will be on view from November 22, 2024 through January 12, 2025.

Exterior View, West Conservatory View from the Main Fountain Garden. Image by Albert Vecerka/Esto. Courtesy of WEISS/MANFREDI.

Paul Redman, President and CEO of Longwood Gardens said "The unveiling of Longwood Reimagined marks not only a milestone for Longwood Gardens but also a bold leap into the future of defining what it means to be a great garden of the world whose foundation is based upon horticultural excellence. This project honors our legacy by embracing innovations and sustainability practices that define 21st century garden artistry. We’re excited to invite our guests to experience the newest addition to our collection of world-class gardens with the unparalleled beauty and creativity that WEISS/MANFREDI and Reed Hilderbrand have brought to life through this transformational journey. With new spaces to explore and dynamic landscapes that evolve with the seasons, Longwood Reimagined ensures that every visit will offer a fresh, immersive experience."

Exterior View, West Conservatory. Image by Albert Vecerka/Esto. Courtesy of WEISS/MANFREDI.

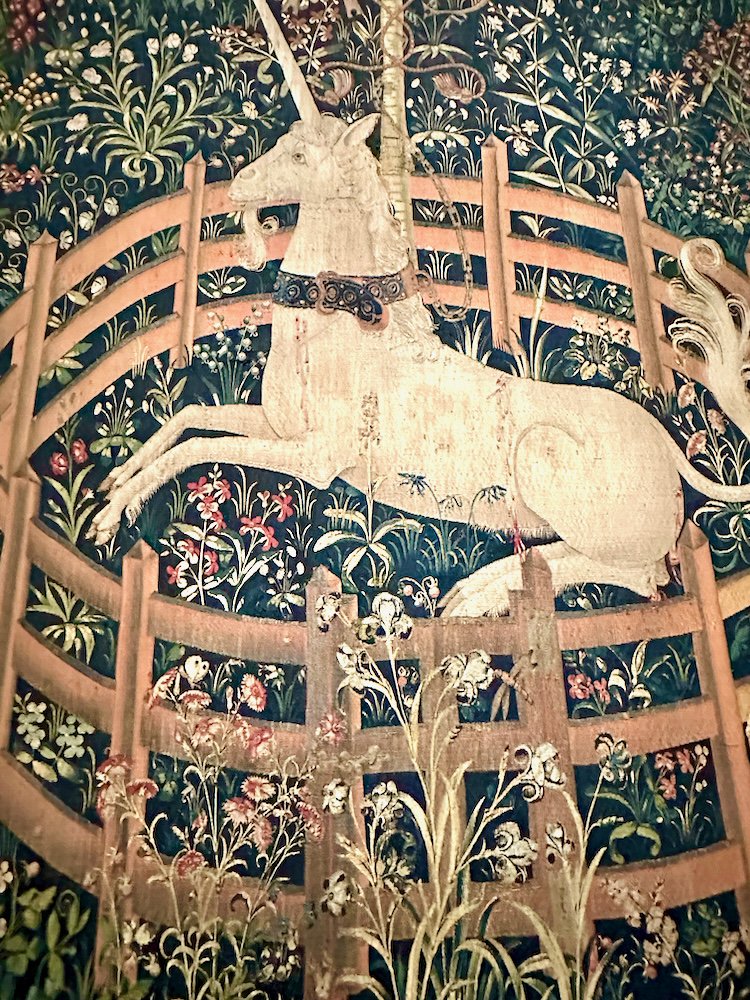

A GLASSHOUSE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

In keeping with Longwood’s tradition of blending fountain gardens and horticultural display, the centerpiece and largest single element of Longwood Reimagined is a new 32,000-square-foot glasshouse, designed by WEISS/MANFREDI. Inside is an immersive Mediterranean Garden featuring planted islands, pools, canals, and low fountains, designed by Reed Hilderbrand. The new West Conservatory with its asymmetrical, crystalline peaks appears to float on a pool of water, while inside, a unique garden under glass evokes the character of the Mediterranean, where both wild landscapes and cultivated gardens express an inseparable relationship between water, stone, and plants.

Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi, principals of WEISS/MANFREDI and lead designers of Longwood Reimagined, whose involvement began over a decade ago, said: “We’re inspired by the sense of discovery and innovation that are defining signatures of Longwood Gardens. We envisioned this transformation of 17 acres as a cinematic journey, a sequence of experiences that range from intimate to grand, reshaping the western grounds into a cultural campus that brings Longwood into a new century. With the West Conservatory as the centerpiece of this newly conceived crystalline ridge, the pleated roof, branching columns, and tapered perspectives extend the marriage of architecture and horticulture that is intrinsic to Longwood's identity.”

Building on the great 19th-century tradition of glasshouses through new sustainable technologies, the West Conservatory is a living, breathing building. Prioritizing sustainability, 128 geothermal wells have been drilled approximately 315 feet deep and are connected to a ground-source, multi-stage heat exchanger that provides heating and cooling to the lower level of the new conservatory, administration building, and the lower reception suite. The main level of the West Conservatory relies on year-round passive tempering of fresh air provided by 10 earth ducts, which are 300-foot long, three-foot diameter tubes, buried under the south slope of the gardens. As fresh air is drawn through the earth ducts, it is warmed or cooled by the earth depending on the season. The earth-tempered air is introduced to the space at the pedestrian pathway to provide passive thermal comfort for occupants and visitors. This innovative design means that the building increases the effectiveness of natural ventilation and reduces the dependence on mechanical cooling in hot weather and supplemental heating in cold weather.

Interior View, West Conservatory. Image by Ngoc Minh Ngo. Courtesy of Reed Hilderbrand.

A MEDITERRANEAN TAPESTRY

Inspired by the gardens and landscapes of the six global Mediterranean ecozones (the Mediterranean Basin, South Africa's Cape Region, coastal California, Central Chile, and Southwestern and South Australia), the West Conservatory garden incorporates three planted islands set on an expansive sheet of water.

Sixty species of plants compose the tapestry of the permanent garden. Drifts of low shrubs and perennials carpet the islands, many with tufty, billowy forms and small leaves that reflect the plants’ response to the scarcity of water, infertile soils, and windswept conditions of this ecozone. The composition includes a range of iconic plants: Agaves (Agave), Aloes (Aloe 'Johnson’s Hybrid’), Blueblossom (Ceanothus griseus var. horizontalis ‘Yankee Point’), and the tiny pink flowers of Deltoid-leaved Dewplant (Oscularia deltoides) that hug the ground. A slightly taller shrub layer expands the garden’s texture and includes the evergreen pincushion shrub (Leucospermum ‘Brandi Dela Cruz’); the dense Egg-and-Bacon plant (Eutaxia myrtifolia), which is known for its two-toned yellow and red-brown flowers; and the aromatic Prostanthera rotundifolia known for its fragrant purple flowers.

Rows of Cypress (Cupressus sempervirens) and Bay Laurel (Laurus nobilis) move through the drifts, framing spaces and gradually disclosing the garden. Trellis structures covered in espaliered citrus define each end of the garden. Vine structures cantilever over and shade the south walk. Canopy trees, including acacia (Acacia salicina) and palm (Bismarckia nobilis), take advantage of the conservatory's height, providing shade for visitors below. Above the east and west entrances, more than 60 baskets of the trailing succulent Baby Burro’s Tail Sedum (Sedum burrito) hang like blue-green clouds, drawing visitors’ eyes to the soaring supports and arched roof of the conservatory. Throughout the year, a series of 90 seasonal plant species will be introduced throughout the permanent plant collection, expanding bloom and diversity within the garden.

Kristin Frederickson, Principal at Reed Hilderbrand said, “Designing the landscapes for Longwood Reimagined has been a deeply rewarding experience. We approached this project with a commitment to creating immersive gardens that both celebrate the richness of Longwood’s existing collections and expand them for the next century. The high ridge of the property, home to Longwood’s conservatories, is now extended west to the iconic Brandywine Valley landscape. Visitors are drawn to the new West Conservatory and Bonsai Courtyard and the restored Cascade Garden along generously scaled promenades and shaded overlooks that highlight the changing seasons and Longwood’s origin as an arboretum. The pools, fountains, and planted islands of the West Conservatory’s Mediterranean Garden honor P.S. du Pont’s fascination with water in the landscape in an entirely new kind of garden within Longwood’s set of conservatories. With a focus on a permanent collection of plants, the garden celebrates the particular beauty of species that thrive in the Mediterranean’s dry climate, expanding understanding of one of our planet’s most diverse ecozones — its beauty, mutability, and resilience.”

Interior View, West Conservatory. Image by Ngoc Minh Ngo. Courtesy of Reed Hilderbrand.

THE CASCADE GARDEN

The relocation, preservation, and reconstruction of the Cascade Garden, designed by celebrated Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994) and first opened in 1992, is another key element of Longwood Reimagined. The Cascade Garden is Burle Marx’s only surviving design in North America and significantly showcases all of the signature elements of his design expression. This is the first time that a historic garden has been relocated as a whole and now occupies a more prominent position in the Longwood experience.

A new 3,800 square foot, WEISS/MANFREDI-designed glasshouse has been created for the garden, which was formerly installed in a retrofitted space in the Main Conservatory. The new, bespoke space recreates exactingly the vertical rock walls, cascading waterfalls, and clear pools designed by Burle Marx. They form the framework for a dense ensemble of plants found in a tropical rainforest, including palms, bromeliads, philodendrons, and more. The new glasshouse also features updated mechanical systems to improve climate control and sustainability. Adjustments to the garden path were meticulously calibrated to meet accessibility standards without compromising the garden’s design, resulting in a more inclusive and now-ADA-compliant experience. A new courtyard entrance includes an arcing path to the garden’s upper entrance through a grove of magnolias.

AN OUTDOOR GALLERY FOR BONSAI

Longwood is home to one of the best assemblages of bonsai in the nation, with a few specimens in training for more than 110 years. This growing collection is receiving a new, dedicated space as part of the Longwood Reimagined transformation. Designed by Reed Hilderbrand, the Bonsai Courtyard is a 12,500 square-foot outdoor gallery for the display and interpretation of this distinguished collection. The design employs a series of clipped hornbeam hedges to define the space and to develop rooms within it to display bonsai for contemplative viewing. The focused expression of craft in the garden’s details references both Japanese traditions and the artistry of the bonsai themselves. A grove of ten Yoshino cherry trees animate the garden, providing shade and intimacy to the experience of the bonsai.

Among the bonsai on view when Longwood Reimagined opens will be key examples from the Kennett Collection, which gifted more than 50 superlative specimens to Longwood in 2022. The Kennett Collection is the finest and largest private collection of bonsai and bonsai-related objects outside of Asia and its specimens are notable for their lineage, including examples from many of Japan’s most famous nurseries, including the Chinsho-en nursery run by the Nakanishi family in Takamatsu. There are also bonsai trained by world-renowned bonsai artists, including Kimura Masahiko, who is known as "The Magician;" Suzuki Shinji of Japan; and Suthin Sukosolvisit of Boston.

Exterior View, Fountain Room. Image by Ngoc Minh Ngo. Courtesy of Reed Hilderbrand.

NEW LANDSCAPES ENRICH VISITOR EXPERIENCE

The 17 acres of Longwood Reimagined also enrich the relationships between the Conservatories, new and old, and the wider landscape beyond, elevating the visitor experience throughout. In the character of Longwood’s historic landscape, trees provide the armature for moving to and among these new destinations in a variety of ways.

The Central Grove

This new grove lies between the Main Conservatory and the West Conservatory, featuring an allée of ginkgo trees and understory of Lenten Rose and Christmas fern. Guests stroll this inviting space to access the Cascade Garden, the Bonsai Courtyard, and the Waterlily Court.

The Waterlily Court and Arcade

The revitalized Waterlily Court, first opened in 1957 and renovated in 1989 by Sir Peter Shepheard, is now restored and framed by a new arcade designed by WEISS/MANFREDI, bringing renewed focus to this unique collection. This central haven brings together the collection of tropical gardens including the Orchid House, Waterlily Court and Cascade Garden, bridging both the historic and contemporary gardens.

Conservatory Overlook

A new Conservatory Overlook opened in May 2024 offers sweeping views of the Main Fountain Garden and its summer fountain shows from the broad stone step seating. A 700-foot-long promenade follows an allée of Yellowwood and Elm trees that stretch along the ridge, leading guests to the West Conservatory Plaza, where century-old London plane trees frame views of the iconic Brandywine Valley landscape.

Orchid House

In February 2022, Longwood reopened its beloved, historic Orchid House, revealing stunning new floral displays within a hundred-year-old structure that has been thoroughly restored. Returned to its original configuration, a gracious new vestibule welcomes visitors and keeps temperatures steady while seamlessly integrating into the Main Conservatory. The Orchid House now exhibits 50 percent more orchids throughout the year from Longwood’s collection, which is recognized as one of the most important in the world.

A NEW HOME FOR THE 1906 RESTAURANT

Longwood’s popular fine-dining restaurant, 1906, has a new, larger space hidden in plain sight that will elevate Longwood’s offerings in culinary arts to the same level of excellence as its horticultural displays. WEISS/MANFREDI has created a gracious new space by carving behind the historic Main Conservatory’s original retaining wall, creating a vaulted space with generous windows looking out on the iconic Main Fountain Garden. Antique Bronze vaulted mirrors on the opposite side of the room ensure that all guests enjoy views of the Garden wherever they are seated. Outside, a 500-foot-long flowering herb garden attracts pollinators and celebrates the culinary program of the 1906 restaurant and event space beyond.

WEISS/MANFREDI’s thoughtfully designed details include custom furniture that creates an elegant space and atmosphere throughout 1906. The vaulted ceiling, which features a basketweave design, was inspired by the water jets of the Main Fountain Garden. Bespoke rugs installed throughout the space evoke the color and textures seen beneath Longwood's tree canopy, and a custom design mural on the west wall translates the soft morning light in Longwood's Meadow Garden. Selected furnishings were built by hand from wood harvested from fallen trees at Longwood by the Challenge Program, a nonprofit organization located in Wilmington, Delaware.

THE GROVE: EDUCATION AND ADMINISTRATION

Longwood Gardens’ new administrative office hub, The Grove, is built from the foundation of an obsolete building. Now an illuminated nexus of activity and programming, the Grove includes classrooms, office spaces, conference rooms, library, and archive.

ABOUT LONGWOOD GARDENS

In 1906, industrialist Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954) purchased a small farm near Kennett Square, PA, to save a collection of historic trees from being sold for lumber. Today, Longwood Gardens is one of the world’s great horticultural displays, welcoming 1.6 million guests annually and encompassing 1,100 acres of dazzling gardens, woodlands, meadows, fountains, a 10,010-pipe Aeolian organ, and grand conservatory. Expanding on its commitment to conservation, in 2024 Longwood Gardens acquired the 505-acre Longwood at Granogue, a cultural landscape in nearby Wilmington, Delaware. Longwood Gardens is the living legacy of Pierre S. du Pont, bringing joy and inspiration to everyone through the beauty of nature, conservation, and learning. Open daily during the holiday seasons and every day except Tuesday during the rest of the year, Longwood is one of more than 30 gardens in the Philadelphia region known as America’s Garden Capital. For more information, visit longwoodgardens.org.

You Might Also Like