Twig Borers and Girdlers on Oaks

/By Susan Clark, Board Member, Massachusetts Chapter of the American Rhododendron Society

Photo by bert Cregg, MSU

In mid to late summer the ground under our oaks is usually littered with terminal leaf clusters that seem to have been snipped off. I always wondered what caused this loss of healthy twigs as it didn’t seem to be the wind twisting them off; the stems seemed smoothly cut, as though by a mysterious vandal high in the tree tops. I resolved to figure this mystery out and, once again, it’s amazing what a clumsy Google search can turn up. ‘Oak twig loss’ eventually explained the mystery and, no surprise, it turns out to be insect damage.

Two different beetles cause this twig loss in the Northeast. Both are members of the huge Longhorn Beetle family, Cerambycidae, with more than 35,000 species found world-wide. Most species, including the two in the Northeast, have distinctly long antennae (horns?) and eat plant tissue like twigs, stems, and roots. The taxonomy of these beetles is predictably complex and disputed. Curiously, the family name comes from Greek mythology, a story about an unfortunate shepherd, Cerambus, who was a master musician and probably invented the pan-pipes. He became dangerously conceited and eventually lost an argument with some nymphs he had offended with his song lyrics. He was transformed into a large wood-eating beetle with horns.

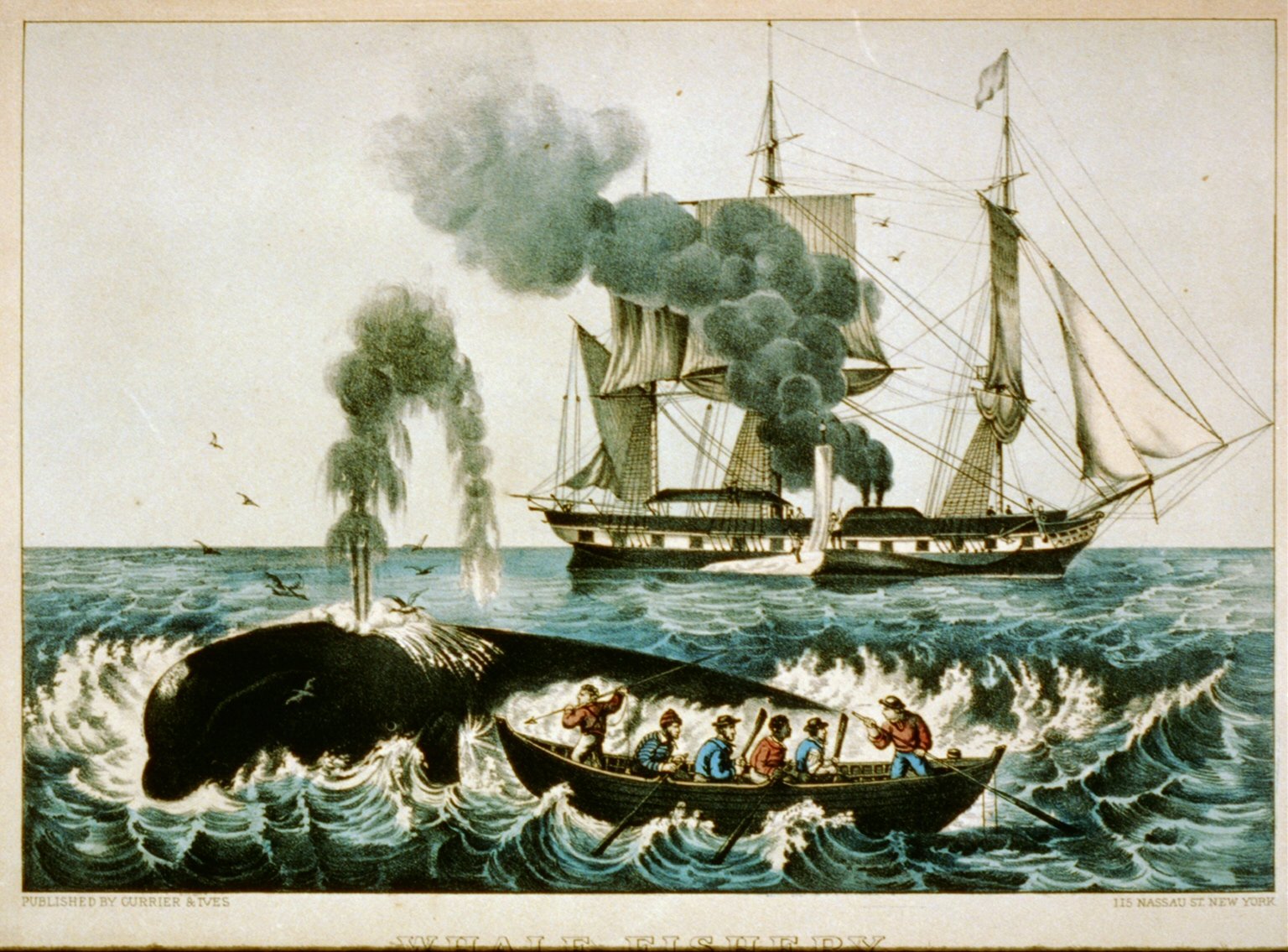

Photo credit: Tim R. Moyer, bugguide.net

Twig Pruner Beetles (genus and species names of this beetle are uncertain and different sites give very different names), are native long-horned beetles, ¾” long, brownish, slender and elongate. They have two posterior spines on each wing cover and their antennae are longer than their bodies. The Twig Pruner prefers oaks but also attacks other hardwoods, like dogwood, elm, honey locust, hickory, but around here it really favors our Red Oaks. When the oaks begin leafing out, these beetles lay their eggs at the tips of the host tree branches up to 1 inch in diameter, one egg per tip. When the eggs hatch, the growing larvae, called roundheaded borers, which are the usual legless white with black heads, bore into the stems and tunnel down them. They winter over inside the twigs, continuing to feed again the next spring. In midsummer they cut around the inside of each branch, but leave the thin cambium layer and bark intact. Eventually the twigs’ weight or the wind snaps them off. Look at the end of a leaf cluster with a Twig Borer and you should see a hole in the inner pith plugged with frass (the beetle poop) to protect the overwintering larvae from predators. The larvae remain inside their now fallen stems, eventually pupating in the twig over the winter, to emerge as adult beetles the following spring when they will fly up into the host tree to lay the next generation of eggs.

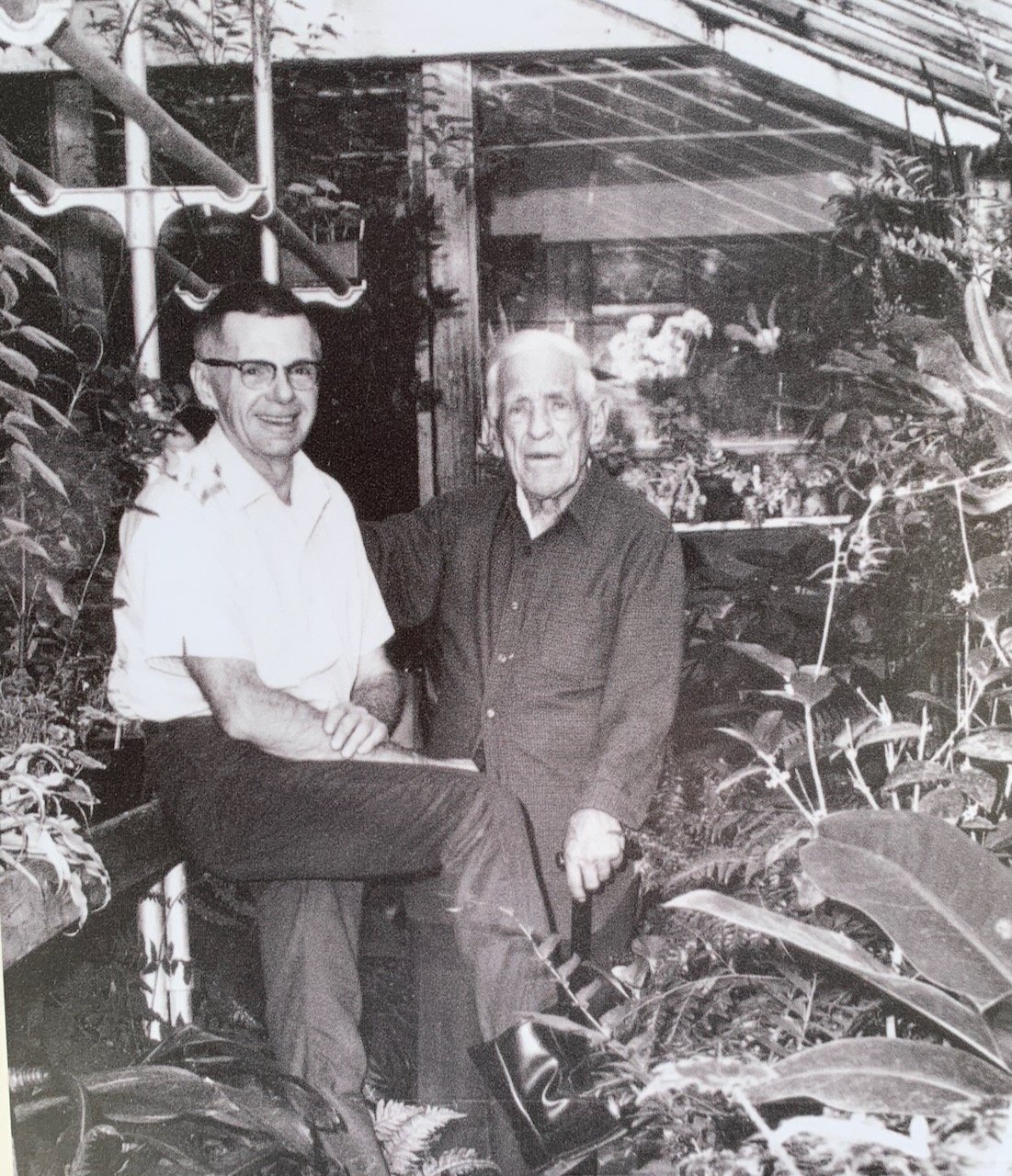

Twig Girdler, Photo from Mississippi state university

A different long-horned beetle, Oncideres cingulata, girdles rather than cuts off the leafy twigs and it has a similar life cycle as the Borer. The Twig Girdler is about ¾” long but it is grey-brown with a lighter stripe across its wing covers (its elytra) and its antennae are about the same length as its body, not longer. Adult beetles emerge in late summer when the females girdle a twig and lay a single egg in the cut portion so their eggs can feed on the dying wood; these larvae don’t eat live wood, unlike the Twig Borer. The girdled terminal quickly falls to the ground that first summer. The Girdler Beetle can be identified by looking at the cut end with its smooth V-shaped outer cut and ragged torn inner wood, quite distinct from the Twig Borer’s cut appearance with the visible tunnel inside. The Twig Girdler larvae bore further into the fallen twig, spending the winter and the next spring inside until they pupate and emerge as adults to start the cycle again.

During late summer, the cut-off twigs, with their green leaves attached, litter the ground under infested trees or worse, they stay snared in unreachable branches, very noticeable and often long-lasting, and to the tidy landscaper, frustrating. Their remarkably persistent green leaves eventually brown but don’t drop off since no abscission cells form as they normally would each autumn for leaf drop. You can diagnose the source of these branches by their ends, a rather smoothly cut surface, very unlike any branches ripped off by the wind.

I have to confess I have never noticed nor identified either beetle; I only saw their littered handiwork. And in a cursory examination of the fallen leafy terminals in my yard, they all seem to be from the Twig Girdler, not the Twig Borer, so each clump of leaves lacks a central eaten-out tube and a frass plug. But I will look more carefully in the future. These beetles do not do much damage to healthy trees, only to the gardener’s peace of mind. The natural world continues to amaze and mystify, but at least I have finally solved another minor mystery.